How does the Christian relate to the Mosaic law? A common approach divides the law into three parts—moral, civil, and ceremonial—and proposes that some parts continue to be applicable while others cease to be applicable. While this division may have some limited role to play within a broader hermeneutical framework, by itself it does not help us to read the OT law as Christians and it seems foreign to the thought of the biblical authors.[1] Leviticus makes no distinction between so-called “moral” uncleanness on the one hand and “ritual” uncleanness on the other, even if some issues seem more intuitively moral to us than others.[2] One and the same condition of uncleanness applies to people, animals, houses, the tabernacle and altar, and the land. Even when applied to people, it includes obviously non-moral issues such as bodily discharges, leprosy, disfigurement, and touching dead bodies. Furthermore, it is all the uncleannesses of the people that require atonement (e.g. Lev 15:31; 16:16), not merely their sins.

There is a different, and better, paradigm for thinking about the way in which Christ fulfills the law, and therefore how we as Christians relate to it. I first became aware of it when reading a chapter by Nelson D Kloosterman,[3] wherein he notes that our thinking about fulfillment has been unhelpfully shaped by the aims of the traditional threefold division of the law: this division encourages us to think about fulfillment in terms of continuity and discontinuity, when instead we should think about it in terms of organic growth and maturity brought about by Christ. Jay Sklar likewise notes that, “If what we see in the Old Testament is an acorn, what we see in Jesus is a magnificent oak.”[4] We could say that Christ fulfills the law by “fully filling it out,” that is, by encapsulating in himself the true substance of which the law is a mere shadow. This doesn’t mean that all laws are equally applicable today as they were when given to Israel at Sinai, but this question is secondary to the more fundamental question of what happened to the law as a whole.

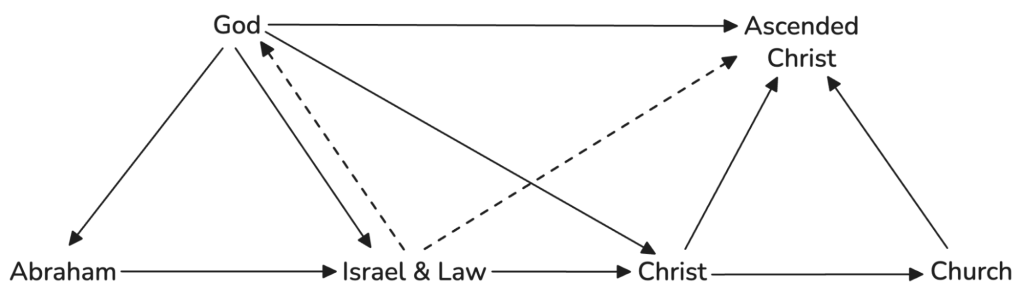

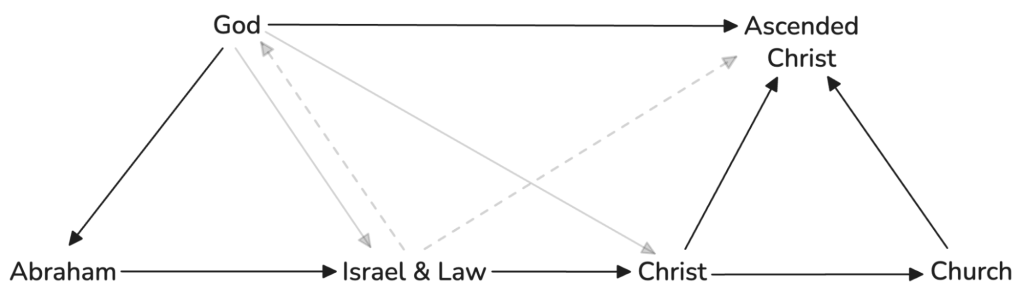

In my paper “Leviticus in Light of Christ,” I started working out the details of this approach for Leviticus, but recently I have been thinking about the law as a whole. I have arrived at a view which can be summarized by the following diagram, which I will unpack in this post:

The top level represents things in heaven, while the bottom level represents things on earth. Solid arrows represent progression or causation of some kind, while broken arrows represent purpose or fulfillment of some kind. The diagram is “commutative” in the sense that any two paths with the same start and end points describe the same process, even if they go through different intermediate points. Consider, for instance, the paths (a) God → Abraham → Israel & Law, and (b) God → Israel & Law. The former captures God’s promises to Abraham and the physical descent of Israel from him, while the latter captures God’s giving the law and establishing Abraham’s descendants as Israel, in faithfulness to those promises. We can analyze sub-diagrams within this larger diagram, and thereby come to a better understanding of law, promise, and their relationship with one another.

The purpose of the law

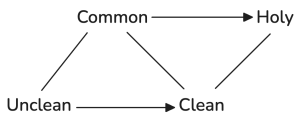

The central part of the diagram tells us about the law, and its relation to Old and New Testament believers. The key thing to realize here is that the law was given by God for a particular purpose, which is captured by the path Israel & Law ⇢ God: the law was designed to draw Israel away from sin and death towards a holy life with God. If God is to be Israel’s God and they are to be his people, as he promised their forefather Abraham, then they need to be guided in avoiding those things which are opposed to God and pursuing those things which are aligned with God. The law encodes this dynamic structure in many different ways. At the most basic level, it condemns idolatry in favor of the proper worship of God, and it condemns sin in favor of justice and mercy. The Levitical system introduces the clean-unclean and common-holy distinctions, which can be understood as follows:

In this diagram, plain lines connect pairs of states which are compatible with one another, such that a person is always in two of them (unclean and common, clean and common, clean and holy). Arrows represent transitions between incompatible states, where the direction of the arrow indicates the preferred direction of the transition. For instance, in Lev 15, if someone is unclean due to bodily discharges, they must first cleanse themselves (unclean → clean) before they may approach God at the tabernacle, thereby moving from the common space of the camp to the holy space of the temple (common → holy). Because the camp is a common area, it may hold both unclean and clean people, but only the clean people may approach the holy temple. The overall intention of this structure is the motion from uncleanness to holiness, which in turn is a motion from death to life with our creator. Cleanness describes the condition of a thing, whereas holiness describes its status in relation to God.[5] Holiness has to do with being set apart for God in some way, where God as supreme creator is paradigmatically set apart from his creation in all its limitations and susceptibility to corruption. When we attend to the full expression of uncleanness in Leviticus, we find that the unifying theme is an association with death and disorder. Conversely, cleanness would be associated with life and order. The creation account in Genesis depicts God as creating by bringing order out of disorder and bringing life from non-life, so that cleanness captures God’s intentions for creatures as their creator. Thus, before one can come into the creator’s holy presence or be put to special use for his sake, they must align themselves with the creatorly intentions by becoming clean.

I realize that the association of uncleanness with death and disorder may not be immediately obvious, so let me summarize the data. Dead bodies make people unclean (Lev 11:24; 21:1; Nu 6:6–12; 19:11–22), while atonement occurs through offerings because their blood is life (Lev 17:11). God’s statutes are living-giving (Lev 18:1–5), while disobeying them brings death (Deut 30:15–16) and makes the people and the land unclean by the practices of the other nations (Lev 18:24–30). Leprosy was associated with death (Nu 12:10–12), and thus was considered unclean (Lev 13–14). Any instances of bleeding, or discharges of semen or blood were considered unclean because this involved a loss of life-giving fluids (Lev 15). This same reasoning applies to postpartum lochia (Lev 12), and the “spilling of blood” on the land through murder (Nu 35:33–34). Finally, animals (Lev 11) are considered clean which conform to the “norm” of that animal’s realm (sea, air, land, c.f. Gen 1:20–25), at least as understood by the Israelites in their ancient pastoral context. Conversely, “those creatures which in some way transgress the boundaries are unclean,”[6] as well as those associated with death in some way, like carrion birds. These boundaries can be transgressed by failing to sufficiently resemble the normative features, as with pigs (11:7), as well as by being mixed or indeterminate in some way, as with swarming things (11:41).[7]

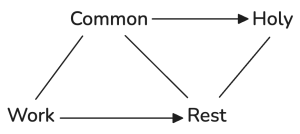

Since uncleanness is associated with death, sin, and disorder, and since holiness is associated with God himself, we see that the Levitical system itself is structured around the very motion I’m saying characterizes the law as a whole: the motion from sin and death to a holy life with God. A similar motion occurs in other cases which don’t have to do with uncleanness, but which follow the same general pattern. Consider the Sabbath pattern, which characterizes many time-related signs in the law:

By calling Israel to hold one day out of seven as holy, God makes the other six days of the week common. The Sabbath pattern of work-then-rest imitates God’s own actions in creation, when he worked for six days and rested (from creating) on the seventh, making the seventh different from the six. In the divine rest of the seventh day, God lived with Adam and Eve in the garden. Now, work was part of the original creation order, so that it would be a mistake to suppose that it is a kind of uncleanness. Nevertheless, work was tainted by sin, so that man must toil in labor to make a living only to one day return to the ground from whence he was taken (Gen 3:19). So, then, God gives Israel the Sabbath pattern of work-then-rest as a sign of their coming out of a broken world into his presence, free from the burden of laborious toil imposed by sin. In the Sabbath pattern Israel repeatedly imitates the motion from sin and death to a holy life with God, in a quasi-return to the life with God before the fall.

This is the unifying meaning of the Sabbath which allows it to be explained in different ways. It is the imitation of God’s creation pattern (Ex 20:11; 31:17), which not only justifies the work-then-rest pattern as a way of holding time holy, but also holds out this original divine rest as the one to which we look, and which we lost at the fall; and it is the sign of God’s redemption of Israel from the labor of slavery in Egypt (Deut 5:15) to the life with God among them in the temple, by which he sanctifies (=makes holy) all of Israel (Ex 31:12–13). It is also why the Sabbath pattern is repeated in multiple ways throughout the calendar and generations of Israel. The holy convocations (Lev 23) are each an instance of Israel coming to God out of the labor of life, to celebrate his redemption and atonement of them; the pattern of work-then-rest is repeated in the Sabbath year, and the Sabbath of Sabbaths, the Jubilee year (Lev 25). Thus, in a very literal sense, the law draws Israel from sin and death to a holy life with God, by having them imitate God’s pattern when he drew creation into existence from disorder, and by having them remember his redemption of them for himself.

The fulfillment of the law

This idea of “imitation” leads to the next point I want to make about the law. In the diagram, there are two paths between God and Israel: God constitutes Israel and gives them the law (God → Israel & Law) while this law draws Israel to a holy life with God (Israel & Law ⇢ God). And yet, this law does not actually bring Israel into God’s heavenly presence, indicated by the fact that there is no solid arrow indicating real progression (Israel → God) but only the broken arrow indicating purpose and fulfillment (Israel ⇢ God). If Israel is not actually brought into God’s presence, but merely orientated in this direction, then how can they actually live with God and thereby fulfill the law they have been given? They cannot, unless God comes down to dwell among them. And this is precisely what he does, by creating a shadow (or earthly imitation) of his heavenly life among the people (Col 2:17; Heb 10:1). Thus, the tabernacle is patterned after the heavenly temple (Heb 8:5; 9:23–25), the priests imitate the true mediator between man and God (1 Tim 2:5; Heb 4:14–5:10; 9:15), the atonement by animal blood imitated the cleansing of death with life (Lev 17: 11; Heb 10:1–4), and the Sabbath pattern is a shadow of the true work-then-rest pattern of God (Col 2:16–17; Heb 3:7–13). This was the furthest the purpose of the law could be fulfilled, for there was no way for sinful humans to enter into the heavenly dwelling place of God.

This is where the rest of the law sub-diagram comes in. “For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do.” (Rom 8:3) The divine Son of God became incarnate as the man Jesus Christ (God → Christ), who died, was raised, and ascended back to the right hand of God (Christ → Ascended Christ), thereby opening up a new, heavenly, possibility for man to live with God (God → Ascended Christ). Because of Christ’s death and resurrection, we may now be incorporated into his new human-divine life by the Holy Spirit.[8] Because of his ascension, this union with Christ means that God has “seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus” (Eph 2:6). Thus, the life to which the law drew Israel has finally been made fully accessible to us in Christ (Israel & Law ⇢ Ascended Christ).

Now, before continuing, let me make two observations. First, notice that the law always had shadows, initially of the life that it could not access (Israel & law ⇢ God), and then later of the life that had become accessible in Christ (Israel & law ⇢ Ascended Christ). It is not only a shadow in hindsight, and it has always pointed us to life with God in heaven. What changed is that Christ made this life accessible to us (God → Ascended Christ), through his incarnation, death, resurrection, and ascension (God → Christ → Ascended Christ). Second, notice that God ultimately fulfills the purpose of the law through Israel, although not in the way they would have expected. This is because Jesus descends from Israel (Israel & law → Christ). Israel fulfills the purpose of the law, because God became an Israelite and “fully filled out” the holy life with God to which it pointed.

This, I take it, is what Paul means by saying that “Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes” (Rom 10:4). The word for “end” here is telos, meaning purpose or goal. The law drew Israel from sin and death to a holy life with God, and in Christ we have the full and heavenly realization of this life. This is also the key, I think, for understanding Paul’s notion of “the law of Christ” (1 Cor 9:21; Gal 6:2). Some have interpreted this as something materially distinct from the law given to Israel, but this has the difficulty of explaining passages in which Paul clearly uses the latter to justify his exhortations to Christians (e.g., Rom 13:8–10; Gal 5:13–15; Eph 6:1–4). I propose that we understand the law of Christ as the law given to Israel as fulfilled in Christ.[9] The law drew Israel to a life with God and Christ gave us access to that life. Thus, the law can serve as a guide for us too, so long as we appreciate the differences between our circumstance and those into which the law was originally given. Suppose you and a friend are in different spots, but searching for the same thing, and your friend has a compass. Even though you are not exactly where your friend is, the reading on their compass can also be a guide for you, so long as you take into account your relative positions. The law is a map for life with God, given to a people before the fullness of that life was available to humanity. Every part of that map can still guide us, although perhaps in different ways. The shadows have given way to their realities, yes, so that we fulfill the purpose of the shadows precisely by clinging to their realities. But the shadows, precisely by being shadows, guide us in their realities.

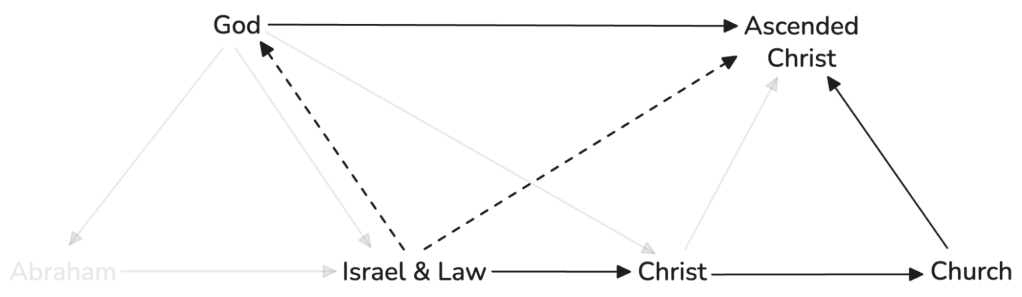

The upshot is that Christ’s fulfillment of the law is the very reason it is applicable to Christians. This is perhaps the opposite of what we would expect, and contrary to what seems to be a common assumption in discussions about law and gospel. The law is the law of Israel, and so by expanding God’s people to include the Gentiles we might expect the law to no longer apply, at least not to the Gentile Christians. Yet, Christ expanded God’s people precisely by making the life intended by the law accessible to all—rather than being centered on the temple within the borders of Israel, it is now in Christ who is accessible to all by the Spirit. Thus, the law which would otherwise not apply to Gentiles as Gentiles is made to be applicable to us in Christ because this life in Christ is precisely what the law has always pointed towards. Put another way, the law is a map and guide of the very life we now have in Christ, the same life which opens up the people of God to include the Gentiles. In short, then, the law applies to us because of its fulfillment in Christ, not in spite of or in addition to it. This relationship is captured by the following sub-diagram:

Knowing why the law is a guide for Christians also informs how we should approach it as one. The original setting of the law is captured by the arrow (a) Israel & Law ⇢ God, whereas our context today is captured by the arrow (b) Church → Ascended Christ. To get from one to the other we need to reckon with two changes.

First, there is the transformation of the heavenly life with God, represented by (c) God → Ascended Christ. We noted above that the heavenly life was not accessible in (a), which is why God gave Israel earthly imitations (shadows) of it, so that they might have a taste of the life to which the law drew them. With the change in (c), these shadows give way to their realities, affecting anything closely related to them in the Levitical system. The temple is no longer a building on earth to which we must approach, but the heavenly temple has been brought into us through the Spirit of Christ. Christ has offered himself as a once-for-all sacrifice, and is our eternal priest in the heavenly temple, so we have no need for the sacrifices or priesthood like Israel did. Since we have entered God’s rest, we no longer need to imitate it in the weekly Sabbath. But if we stop here, paying attention to only how the shadows of the law have ceased, then we have missed the point. We did not lose the shadows in Christ, but gained their realities! Christ fulfilled the law, not empty it out!

It is only partly correct to say that Israel worshipped in a temple but Christians do not. It is more accurate to say that Israel worshipped in an earthly temple but that Christians worship in a heavenly one. If Israel’s earthly temple was nothing like the heavenly one, then it could not have been a shadow of it. The proper Christian approach to the earthly temple is to reflect on how exactly it was a shadow of our current heavenly temple, so that we might properly live with the latter—a task which requires a deep appreciation of the law as well as what the work Christ has done in fulfilling it. Thus, far from making the earthly temple a relic we can ignore, in some sense we need to understand it more deeply than our forefathers did, so that we might tease apart what belongs to the earthly temple as temple from what belongs to it as earthly, or put another way, what it has in common with the true heavenly and what it merely imitates. This same point applies to every shadow of the law.

We could spend entire posts applying this to individual shadows, so I will not attempt that here. My aim at the moment is simply to work out the rationale for such application, so that Christians can think about the law as much as they do the contents of the NT. Nevertheless, let us consider a brief illustrative example. A central part of the Levitical system were the animal sacrifices made at the temple, which were brought to atone the temple (sin and guilt offerings), atone the offerer (burnt offering), and then finally to celebrate and enact fellowship with God (fellowship offering). Christ fulfills this as our once-for-all atoning sacrifice, through whom we have fellowship with God, and we partake of this sacrificial meal every time we eat the Lord’s Supper, just as the offerers would eat of their fellowship offerings under the law. But what about the other aspects of an offering? The very act of offering involves giving (or offering) oneself to God in some way. Under the law, the offerer had to offer the best of their animals and the best parts of those animals before they could eat their share of the sacrificial meal. Through this act of giving, the offerer recognizes that they owe everything to God and so puts him above themselves in humble submission. Certainly this is what Christ did in submitting to the will of his Father to the point of death, but we lose something if we think this means we don’t need to do likewise. This self-offering is part of a healthy life with God, since by it we enact and are reminded of our humble position before him—a greater appreciation of it would surely reduce the chance of pride before others, or the sin of taking God’s grace for granted. How do we enact such self-offering if animal sacrifices are no longer a thing? We offer the whole of ourselves to God, treating every moment as an offering to God in Christ. Note that this is no mere moralization, but a consequence of Christ’s fulfillment of the OT shadow. We are now in God’s presence continuously, rather than briefly for the duration of the offering. Our life now is Christ (Col 3:1–4; Rom 6:1–14), who was the offering in question. What else can we do but live this life out as an offering? As Paul says, “present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your proper worship.” (Rom 12:1)

So, then, the law’s (or Israel’s) temple offerings can guide us because they are the shadow of the reality we have in Christ. It is precisely because they are shadows that they can guide us in living out their realities. The same point applies to all the other OT shadows.

The second thing we need to reckon with when thinking through the movement from (a) to (b) is more straightforward: it is the transformation of the circumstances of God’s people, (d) Israel & Law → Christ → Church. The law was not given in the abstract, but to a people in a particular context, a context which will necessarily have similarities and dissimilarities with our own. Take, for example, the following command:

When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, neither shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. And you shall not strip your vineyard bare, neither shall you gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard. You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner: I am the LORD your God. (Lev 19:9–10)

It would surely be a mistake to say that this command does not apply to us because we do not own farmland. God is using a particular circumstance as the context in which to frame his desire for his people, namely that they would take care of those less able to take care of themselves. This is part of what it means to live the holy life with God, to which the law drew Israel in their particular circumstances and which we now have in full in Christ. Meditating on the law as a Christian therefore requires that we transpose what it says into our own circumstances, that we might know what God requires of us.

But how do we know what belongs to the intention of a law rather than the circumstance? Sometimes the law will tell us, as the command above does when it explains that the purpose is to leave food for the poor and the sojourner. More generally, however, we should approach the law as wisdom literature rather than a modern legal text.[10] The point of the law, like all ancient legal texts, is not to give a comprehensive list of rules, but to outline in broad strokes the kind of community that it wishes to cultivate. It is then up to the community to meditate on the kind of life that is outlined, and figure out how particular cases would fit into that. In other words, we should not try to transpose and apply individual laws in isolation, but the larger tapestry to which they belong. It is in this bigger picture where we see the law’s vision for a holy life with God emerge.

Like the proverbs used in wisdom literature, individual commands are polysemous, having various overlapping senses and values which manifest themselves more clearly when read alongside other commands. The command quoted above is part of a collection of commands all related to our treatment of others, particularly in the interest of justice in different areas of life. On another occasion we might read this command together with other commands about how to use our wealth properly, or how to trust God with our well-being, or how to properly steward the earth, and so on. Meditating on the law requires going beyond individual commands, so that we can more clearly see the multi-faceted intentions of each. The law is more than the sum of its commands.

To summarize, the law is a guide for Christians because of Christ’s fulfillment, not in spite of it. Shadows are guides for us because they are shadows of the realities we now have in Christ. And meditation on the law is a holistic exercise, in response to the polysemous nature of its commands.

The promise and the law

The last thing I want to discuss is how the law fits into the broader story of salvation, its role in redemptive history. Consider what Paul says about this in Romans:

For the promise to Abraham and his offspring that he would be heir of the world did not come through the law but through the righteousness of faith. For if it is the adherents of the law who are to be the heirs, faith is null and the promise is void. For the law brings wrath, but where there is no law there is no transgression. That is why it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his offspring—not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham, who is the father of us all, as it is written, “I have made you the father of many nations”—in the presence of the God in whom he believed, who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist. (Rom 4:13–17)

He makes a similar point in Galatians, in a different polemical context:

This is what I mean: the law, which came 430 years afterward, does not annul a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to make the promise void. For if the inheritance comes by the law, it no longer comes by promise; but God gave it to Abraham by a promise. Why then the law? It was added because of transgressions, until the offspring should come to whom the promise had been made… (Gal 3:17–19)

The salvation story begins in earnest when God promises Abraham that he would reconcile the world to himself through Abraham and his descendants. He promises that he will bless the world through Abraham and his descendants, thereby undoing the curse that had been introduced at the fall. This same promise is also framed in terms of Abraham becoming the father of many nations, as well as inheriting the land and eventually the whole world as God’s blessing extends to all people and all places. All of this is included in the notion of inheritance (or being an heir)—the land, the family, the blessings, and ultimately inheriting God himself (Rom 8:17). Paul’s point is that since this covenant was originally based on a promise, and we see it given to Abraham’s children by the promise, it would make no sense for God to later require that we somehow earn it by submitting ourselves to the law. Rather, it must always be by the promise, and the law must simply support this promise.

The Mosaic covenant was not a replacement of or alternative to the Abrahamic covenant, but a (partial) fulfillment of it. This is evident from the fact that the basis of the covenant was God’s fulfillment of his promises to Israel’s forefathers (Ex 2:23–3:22), as was the mercy he promised to show them when they rebelled (Lev 26:4–42). It is even from the fact that he saved Israel from Egypt before giving them the law, not after. From beginning to end Israel was the people of God through the promise rather than obedience to the law. Herein we may understand the promise-law antithesis: for inheritance to come by the law it must come simply by doing (or trying to do) what it says rather than receiving by faith the promise from God, however he sees fit to fulfill it. Thus, if the inheritance came through the law it could no longer come through the promise.

What, then, is the place of the law? Paul says that it was added because of transgressions. The law guided Israel in their life with God, in fulfillment of the promise to Abraham to be their God and they his people (Gen 17). In order to do this, we have said that the law draws Israel from sin and death to a holy life with God, so that it must necessarily condemn sin as contrary to this life, as something to avoid and escape. The law was not the means by which they became righteous—by which we enter into this relationship or even maintain this relationship—but rather described what this relationship looks like. Note that I’m not suggesting where we enter the covenant by grace but stay in by works. Both entering and remaining in the covenant are from faith and by grace, based on God being faithful to his promises to Abraham. Rather, we should think about this like we think about the relationship between faith and works: receiving the promise by faith daily is the basis for Israel’s relationship with God, and the law described how they were to live out this relationship with him. Why then does the law say the person who does these laws shall live (Lev 18:5)? For the same reason that Jesus rejects those who call him Lord but practice lawlessness (Matt 7:21–23) or that Paul says faith without love is nothing (1 Cor 13:2). Our works characterize the manner in which we receive the promises by faith, so that a rejection of the law is a failure to have the proper faith.[11] Proper faith in the promises of God works itself out in obedience—after all, what is received by faith is what is promised, and what is promised is a life with him as our God, which can only be embraced by a faith which produces obedience.

Here we return to the fundamental limitation of the law, that though it pointed Israel to a heavenly life with God it could never achieve such a life for them. As such, it could not help but condemn the sin which required God to be kept at arms length at all times. The law’s clean-unclean antithesis serves to condemn Israel along with the nations, so that “the whole world may be held accountable to God” (Rom 3:19; Gal 321–22). Israel had been separated from the uncleannesses of the surrounding nations to live in God’s holy presence (Lev 18:1–5, 24–30; 20:22–26), but even then they had to ensure that they never approached God at his temple when unclean (Lev 15:31). The constant animal sacrifices, the priesthood, the imitation of God’s rest—all of these reminded them that though God was among them he was still in some sense unreachable, hidden in the temple, because of their ever-present sin. Perhaps we only see the limitations of the law in hindsight, when the fullness of the promised life with God has come in Christ. This is where the outer sub-diagram comes in:

On the left-hand side we see God giving the promises to Abraham (God → Abraham). At the top we see God fulfilling this by transforming the heavenly life into something accessible to us (God → Ascended Christ), and at the bottom we see that this is achieved through Christ (Abraham → Israel&Law → Christ → Ascended Christ). The right-hand side tells us that ultimately we have access to this life through union with Christ: because Christ has ascended (Christ → Ascended Christ) we can be seated with him by being found in him (Christ → Church → Ascended Christ). Comparing the left- and right-hand sides of the diagram, we see that the direction of the arrows is inverted: God comes down to earth in order to give Abraham the promises, which he ultimately fulfills by raising Abraham’s children up to a heavenly life with him. Two things are worth noting before we close.

First, this overarching fulfillment of the promise helps us see what Paul means when he says that the law was a guardian until Christ came (Gal 3:24). God’s people are under the law for most of the span of time between Abraham and Christ (i.e. the whole of Israel & law → Christ). It was not a replacement of the promise, as we have seen, but a support for it until the fullness of the promise was revealed in Christ. Now that the fullness has come, we are no longer under the care of the guardian, which is to say we are no longer under the law. This is a natural consequence of the inclusion of the Gentiles—we have been ingrafted into Israel (Rom 11:11–24), yes, but we have ingrafted as Gentiles, so that the law which divided Israel and Gentiles is no longer in effect as it once was. Again, we must remind ourselves to not be too hasty in discarding the law. We are no longer under law because it was a guardian until Christ had come, but by being a guardian it prepared us for life in Christ, so that it can now guide us in the life we have.

Second, I should clarify the nature of the heavenly life to which we now have access in Christ. We currently have this life in an already-not-yet manner, so that Paul can say that we are already seated with Christ in the heavenly places (Eph 2:5–6), hidden in God (Col 3:1–3), alive to God (Rom 8:9–10), etc., but also that we do not yet have the fullness of these things (Eph 2:7–9; Col 3:4; Rom 8:11). The OT spoke of two ages: the present age and the age which would be ushered in by the Christ. If that was all we had to go on then we would be forgiven for thinking that the former will end as soon as the latter begins. But because Christ before the end of time, we are now in a time when these two ages overlap. In this twilight of the ages we in some sense have one foot in the previous age and another in the next, which is why Paul urges us to walk according to the Spirit rather than flesh (Rom 8:1–11; Gal 5:16–26). Christ has fulfilled the law, yes, but this fulfillment will only be brought to completion when he returns, bringing an end to the previous age. Until then, we still only see dimly (1 Cor 13:8–13), and are in need of a guide for the heavenly life to which we already have access through the Spirit who indwells us. When that time comes, the Spirit will remake us with glorified bodies like that of Christ (Rom 8:11; 1 Cor 15:35–58), that we would be completely drawn from sin and death to the holy life with God.[12]

Conclusion

In the chapter from Kloosterman I mentioned earlier, he proposes that we need to change the questions we bring as Christians to the law. Instead of asking “does this law continue to apply today?” we should rather ask “how is the true substance of this law filled out in Christ, and how should we therefore think about it in light of his work?” In this post I have proposed an account of the law within God’s unfolding plans which I hope helps us ask this second question. To summarize the proposal, the purpose of the law was to draw Israel from sin and death to a holy life with God. Though we are not under law, in Christ we have the life to which it pointed and therefore it can be a guide for us as we seek to live out this life. This is to say, rather than making the law less applicable to us, Christ’s fulfillment of it is the basis for it being applicable to us as well as the lens through which we use it as a guide. Finally, though the law is holy and good (Rom 7:12), we must not elevate it beyond its role as a guardian and guide to the life that we have through the promise, received by faith.

[1] Christopher J. H. Wright, “The Ethical Authority of the Old Testament: A Survey of Approaches, Part I,” TynB 43 (1992): 205.

[2] Anthony Cothey, “Ethics and Holiness in the Theology of Leviticus,” JSOT 30.2 (2005): 131–151.

[3] Nelson D. Kloosterman, “The Old Testament, Ethics, and Preaching: Letting Confessional Light Dispel a Hermeneutical Shadow,” in Living Waters from Ancient Springs: Essays in Honor of Cornelis Van Dam, ed. Jason Van Vliet (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2011), 189–90.

[4] Jay Sklar, Leviticus: An Introduction and Commentary, TOTC 3 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2014), 139.

[5] Michael L. Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord? A Biblical Theology of the Book of Leviticus (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015): 155.

[6] Gordon J. Wenham. 1981. “The Theology of Unclean Food,” Evangelical Quarterly 53 (1): 6–15.

[7] For further discussion on all this, see Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord? (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015): 153–67.

[8] See my paper, “Anastatic Theory of Atonement,” TheoLogica: An International Journal for Philosophy of Religion and Philosophical Theology 9 (2025).

[9] This is not unlike the phrase “Spirit of Christ”. The Spirit of Christ is the same person as the Spirit of God, namely the Holy Spirit. But he is described as the Spirit of Christ in light of his role in salvation, after Christ’s resurrection and ascension. Likewise, the “law of Christ” is the “law of God” in the OT, now understood through the lens of Christ’s salvific work.

[10] For a great introduction to thinking about the law in terms of wisdom, see John H. Walton and J. Harvey Walton, The Lost World of Torah: Law as Covenant and Wisdom in Ancient Context.

[11] I have unpacked this in more detail in an earlier post, “Judgment according to works in Romans 2.”

[12] I have discussed this two-stage fulfillment in more detail in a lesson I did, “God’s Spirit Among His People.”

Leave a comment