In response to my previous post, the anonymous reader whose question prompted it asks: “what argument do you think is considerable against existential inertia?” The idea of existential inertia has been around for a while, but has received its most detailed analysis and defense in recent years thanks to the work of Joe Schmid and Daniel Linford, in their book Existential Inertia and Classical Theistic Proofs. Prior to this, the two had co-authored a huge blog post on the topic, “So you think you understand Existential Inertia?” (henceforth cited as “So You Think”) As I mentioned in my previous post, I have not had the chance yet to sit down and read the book. I have, however, read most of the blog post, and thanks to its detailed table of contents can reference individual parts of it. Before starting, it is worth pointing out, as Schmid has done so repeatedly, that the dialectical context in these discussions is important. In this post, my aim is simply to articulate what I think about existential inertia as a Thomist. In particular, this means that I take for granted certain metaphysical and natural philosophical conclusions, the defense of which far exceeds the scope of a blog post.

So, what is existential inertia?

In simplest terms, EIT [the Existential Inertia Thesis] is the claim that at least some temporal concrete objects persist in the absence of both (i) sustenance or conservation from without and (ii) sufficiently destructive factors that would destroy the object(s). EIT does not aim to answer that in virtue of which objects persist; instead, it purports merely to describe the way they persist. EIT can (and should) be supplemented with an answer to the aforementioned question. Such answers represent inertialist-friendly metaphysical accounts of persistence. (So You Think, 2, emphasis original)

As a way of highlighting the distinction between a description and account, note that Schmid avoids even saying here that existential inertia is a tendency for staying in existence, because this would already be the beginning of a metaphysical account. Now, the Thomist actually agrees that existential inertia obtains in a variety of senses, for both accidents and substances. Nevertheless, we think that all beings other than God depend on God’s causal activity in order to remain in existence from one moment to the next. The reason we can affirm both things comes down to how we understand the real distinction between essence and existence, which I will explore through the lens of Aquinas’s De Ente argument for God’s existence.

1. Preliminaries

In On Being and Essence (Latin: De Ente et Essentia), Aquinas spends the first few chapters explaining what essence is and how it relates to being. When we consider some being as a whole, we can consider it inasmuch as it is what it is, which is its essence, and we can consider it inasmuch as it simply is, which is its esse (existence). Essence is sometimes referred to as that in virtue of which a thing is what it is, and while this is true so far as it goes, to make it more precise we need to add the qualification “as a whole” somewhere. One of the things Aquinas discusses in these earlier chapters is how the human essence is different from humanity: Socrates is human, but he has humanity. “Humanity” refers only to the form of Socrates, whereas “human” refers to him as whole, including both form and matter. Starting with a conception of the individual Socrates, we can get to a universal conception in at least two ways, which corresponds to this difference between human and humanity. If we abstract away any consideration of matter whatsoever, then we are left with the form only, humanity. On the other hand, if we abstract away only the individual matter of Socrates (“this flesh and these bones”) while retaining the notion of matter as such (“flesh and bones”), then we are left with a universal essence, human. Both Socrates’s form and essence are principles in virtue of which he is what he is (a human), but his form only accounts for this in part while his essence accounts for it as a whole.

These and other points take up Aquinas’s time for the first three chapters of the De Ente. It is only in the fourth chapter that he finally gets to discussing the relationship between essence and esse. He starts by showing that these are in fact distinct concepts, rather than merely distinct ways of talking about the same concept. Sometimes it’s obvious that two ways of thinking about something give us the same concept, as in the case of synonyms like “bachelor” and “unmarried man”. Other times, however, it’s less obvious, as in the case of geometric identities like “polygon with three sides” and “polygon with three interior angles”, both of which refer to the same shape, a triangle. In the case of essence and esse, Aquinas reasons that they cannot in general be the same concept, since we often know the essence of a thing without knowing whether it exists—as in the case of a human, or a phoenix. Even though we don’t know every detail of the human essence, our conception of it nevertheless covers all the parts in one way or the other (form, matter, animality, rationality, materiality, etc.) and yet we cannot determine from any of this whether a particular human exists. So, at least in general, essence and esse must pick out different concepts.

2. The multiplicity argument for the real distinction

But do these distinct concepts correspond to really distinct features of a thing (like a heart vs a leg), or do they pick out the same reality (like Superman and Clark Kent)? Sometimes we can determine this directly, by arguing or showing that two features are separable from one another, and therefore really distinct. But if essence is really distinct from esse then they will never be separable, because the esse makes the essence exist while the essence makes the essence this rather than that. Something can neither exist without existence nor without being what it is, and so essence and esse never exist apart from one another. For this reason, Aquinas provides an indirect argument for their real distinction.

The first stage argues that there can be at most one thing whose essence is really identical to its esse. In order to show this, he considers the ways in which something may be diversified. The alternatives he considers are specific to his metaphysical framework, but we can see the common thread between them by generalizing them slightly. Some X can be plurified if (1) X receives diverse things into itself, as a genus receives specific differences into itself in order to make the species, (2) X is received into diverse things, as a form is received into diverse matters to make individuals of the same species, or (3) X is found unreceived in one thing and received in another. Note that the X we’re considering here is something abstract, which may be found in concrete things in more than one way. Thus, in the third case, X is diversified first by being found in both the unreceived and the received and second by possibly being received into diverse things.

We can justify this set of alternatives as follows. If X is common between two things then it is that in virtue of which those two things (at least in part) are the same. Thus, there must be something else in virtue of which they are distinct, for otherwise they would be entirely the same.[1] In order for two such opposing principles to coexist in a single thing without devolving into contradiction, it must be the case that one of them is open to the other. Whenever something is open to Y, then of itself it is neither Y nor non-Y but can be composed with it in some way, which we describe as X receiving it. So, we have three possibilities: (1) the common receives diversity, (2) the diverse receives commonality, and (3) the common can be unreceived[2] as well as received into another.[3] There is no fourth option wherein the common is unreceived and receives diversity, because if X is common and open to Y or non-Y, then X of itself is neither Y nor is it non-Y. But in order to exist X must be one of these two alternatives, and whichever it is would be received by X. Thus, the alternatives considered by Aquinas (understood generally enough) are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive.

Aquinas next applies this distinction to the case of a being whose essence is really identical to its ease. Such a being would have to be pure or absolute esse, since the whole of what it is is just esse itself.[4] Now, it’s not possible for pure esse to receive some difference, as in (1), or be received into something else, as in (2), since in either case it would cease to be pure. In either case it would be qualified by the X which receives it or which it receives, and thereby be an X-esse (compare: a rational animal, and an individual human). This leaves us with (3). In this case, pure esse would be diversified by existing as unreceived esse on the one hand and as received on the other. But this latter case would require (1), which we have already seen is impossible. Thus, pure esse cannot be plurified, so that there can be at most one being whose essence is identical to esse.

Now, if there were such a being, then esse (rather than pure esse) would be plurified according to (3), existing as unreceived esse on the one hand and received on the other. This unreceived esse would be precisely the being of pure esse, since by being unreceived it is not qualified in any way or added to anything else. In everything else, essence must receive esse as something distinct from it. Furthermore, since esse is a kind of act and essence receives it, that essence is itself in potentiality to esse as its act.[5]

3. Some clarifications

Before continuing, let me make some clarifications about what the multiplicity argument does and does not entail.

First, we may worry whether something like the principle of Identity of Indiscernibles (IoI) is lurking somewhere in the background here. The principle has two equivalent formulations:

(IoI1) If two things agree on all their properties, then they are identical.

(IoI2) If two things are distinct, then there is some property on which they differ.

This “differing property” in IoI2 looks a lot like the “something else” in our explanation of the distinction made by Aquinas. However, we must keep in mind that in Aquinas’s argument we’re not talking only about the properties a thing may or may not have, but also the constitutive principles of its nature and being. To illustrate this point, consider the symmetry problem for IoI:

The Principle often gets called into question, however, when we consider qualitatively identical objects in a symmetrical universe. Consider, for instance, a perfectly symmetrical universe consisting solely of three qualitatively identical spheres, A, B and C, each of which is the same distance, 2 units, away from the others. In this case there seems to be no property which distinguishes any of the spheres from any of the others.[6]

From our perspective this would not be a problem, for all that interests us is that “sphericity” has been plurified by being received into three distinct parcels of matter. Whether it is possible to determine which is which is secondary to whether they are distinct from one another—the latter but not the former is prior to them being any number of units away from one another. Thus, while Aquinas’s argument looks a bit like it depends on a controversial principle like IoI, in fact it goes much deeper and is about more basic features of reality. It concerns itself with what makes distinction between things possible in the first place, not with how to determine which is which. It concerns itself with diversification, not with identification.

Second, we may wonder whether the multiplicity argument shows that essence and esse are really distinct or merely really non-identical. In some sense “distinct” and “non-identical” are synonymous, but the Thomist needs more than this—speaking mereologically, we need them to be disjoint from one another. Now, if they are non-identical but not disjoint, then there will either be some non-exhaustive overlap between them or esse will be a part of the essence of a thing, and we can show that neither of these can be the case. First, if esse extends to something other than the entirety of some essence E, then what it realizes (and therefore what exists) is not an E, but something else, since it is the essence which governs what a thing is. But, if a thing’s esse is (or non-exhaustively overlaps with) some proper part of its essence, then that thing’s existence would be prior to the realization of the entirety of its essence, and so it would exist without being what it is—a contradiction.[7] Second, when essence and esse are non-identical, then they fulfill opposing functions within the constitution of a thing: esse unifies all things qua existing while essence diversifies them, and essence receives while esse is received. If esse shared something with essence, then there would need to be at least some overlap in their function, but there is none. Thus, if esse and essence are not identical, then they must be really distinct.

Third, we may wonder why there couldn’t be multiple beings of pure esse, so long as each one’s essence is identical to its own esse rather than the other’s. The upshot of the multiplicity argument is that esse as such is individuated precisely by its composition with essence, which limits and diversifies it. Thus, apart from its reception by a distinct essence, esse is not individuated to this or that thing, or indeed limited or qualified in any way. Accordingly pure esse, which is not received by a distinct essence, is not individuated into this or that esse at all, but is subsistent esse itself.[8] And further, it is esse itself which is received by each essence, resulting in this or that esse belonging to this or that thing.

4. The causal principle and existential inertia

Having established that there can be at most one being whose essence is identical to esse, Aquinas proceeds in two more stages to show that there is at least one such being, and therefore that such a being exists. In the next stage, then, he proceeds as follows:

Now, whatever belongs to a thing is either caused by the principles of its nature, as the ability to laugh in man, or comes to it from some extrinsic principle, as light in the air from the influence of the sun. But it cannot be that the existence of a thing is caused by the form or quiddity of that thing─I say caused as by an efficient cause─because then something would be its own cause, and would bring itself into existence, which is impossible. It is therefore necessary that every such thing, the existence of which is other than its nature, has its existence from some other thing. (§80)

It is this passage where Aquinas deals with questions most directly related to existential inertia, although you’d be forgiven for missing it given his brevity. Consider the causal principle he articulates: whatever belongs to a thing is caused by the principles of its nature (individually or together) or something external. The first part of this covers all sorts of things, including existential inertia. Aquinas mentions risibility, which is a classic example of a power which flows from our rationality. We can add to this any of the vegetative, animal, or rational abilities that we have by virtue of our form and matter working together as they do. On the other hand, learned knowledge, being lifted up, sunburn, habits, sustenance, and all sorts of other things are the results of external causes, at least in part.

Inertial phenomena are interesting because to some extent they arise from both external causes and the principles of nature. An external cause is needed to accelerate a brick to a particular velocity, but after this acceleration finishes the brick continues to move along this velocity unless impeded by other forces. The brick’s nature, like all physical natures, orders it to maintain its velocity without determining it to any specific velocity. Thus, by nature the brick preserves whatever velocity is given to it by an external cause. The same goes for many other accidents besides velocity. If an object is painted red, for instance, it will remain red until painted some other color or wear-and-tear erodes the red paint. The accidental form of redness is preserved by the substantial form it qualifies, the latter of which is determined to maintain its color without being determined to a specific color.

This brings us to the preservation of things in existence, or existential inertia. Recall that matter is an otherwise indeterminate substratum and form is what determines it to this or that way of being. Prime matter is entirely indeterminate, only in potential to being without contributing any actuality of its own. Thus, in determining prime matter to this or that kind of being, the substantial form also makes it into a substance which is ordered to its own preservation. This “substantial” inertia (as opposed to the “physical” inertia and “accidental” inertia described above) is therefore precisely existential inertia, since it preserves the substance in existence from one moment to the next. For example, the substantial form of a living thing (called the “soul”) orders the parts so that they mutually build one another up and preserve the life of the organism, thereby keeping in existence from one moment to the next. The substantial forms of non-living things are likewise ordered to keep them together, albeit in a much more basic and less obvious way. So, then, from a Thomistic perspective, existential inertia is covered by the first of the two options mentioned by Aquinas’s causal principle: it is caused by the principles of a thing’s nature.

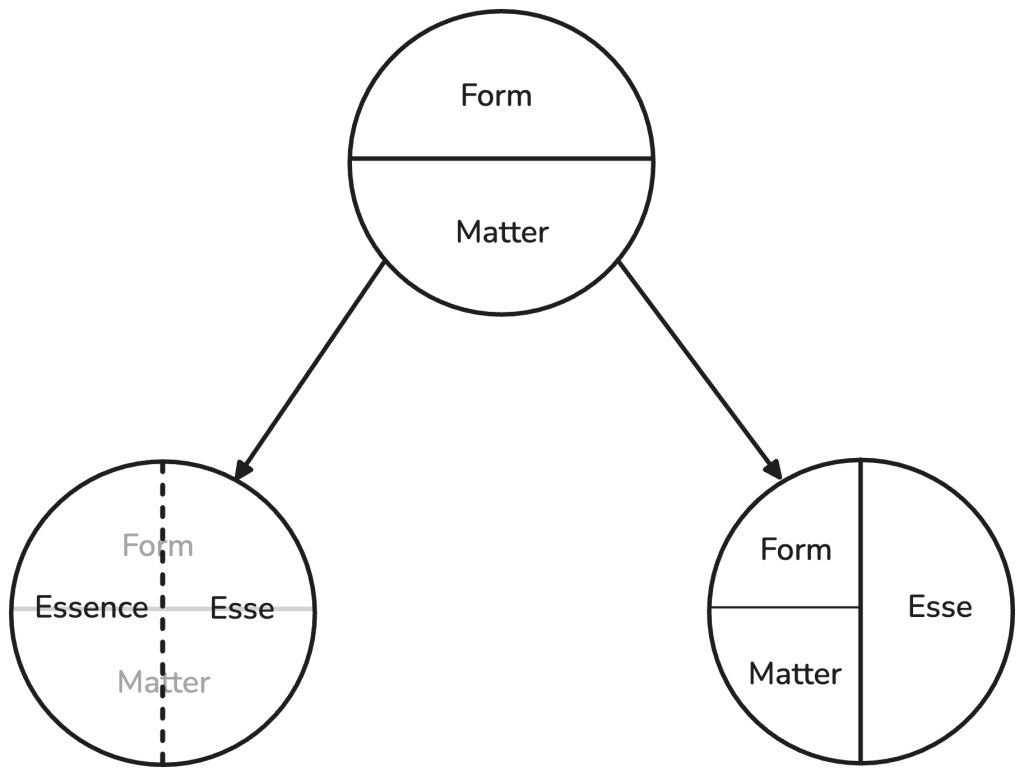

Why, then, does Aquinas go on to say that, “it cannot be that the existence of a thing is caused by the form or quiddity of that thing”? Because of the real distinction! Form and matter make up the essence of a thing, and in all but one thing essence is really distinct from esse. As already mentioned, when they are really distinct essence is in potential to esse and esse is its actualization. Just as the continued determinacy from substantial form is what accounts for the continued actualization of matter, so too so we need something to account for the continued actualization of essence. After all, as I have previously and recently explained, potentiality as such is indifferent to whether it is actualized or not, since by its very nature it is open to both alternatives. Thus, while substantial form overcomes the indifference of prime matter, the real distinction shows us that essence (which includes both form and matter) is itself indifferent on a deeper level. The matter-form distinction is caught up in this broader essence-esse distinction, so that the composition of the former is operative within the composition of the latter. We can illustrate this as follows:

In the first image, we have just the matter-form distinction, whereas the second and third images capture two ways in which this might relate to the essence-esse distinction. In the left option, essence and esse are two ways of talking about the same underlying reality, namely the matter-form composition. That is, for esse to actualize essence just is for form to actualize matter. In this picture, essence and esse are really identical, the only difference being in how we consider matter and form. In the right option, the matter-form composition is contained within the essence, so that the essence-esse composition is something which happens in addition to the matter-form composition. Without additional reasons for preferring the right option, the left looks simpler and even more intuitive. But the multiplicity argument gives us exactly these sorts of reasons, since the left option assumes that essence and esse are really identical while the right assumes that they are really distinct. So, we need to reckon with the implications of the latter.

How, then, does substantial form relate to esse? Both actualize something, but they work in orthogonal and complimentary ways: the substantial form makes matter to be this or that kind of being, while the esse makes the essence to simply be. We can also consider this the other way around: the prime matter diversifies this or that form into this or that individual, while the essence diversifies esse at all. Form has some intrinsic diversity in it, whereby it orders matter to a particular kind of being, while esse has no diversity of its own, since it determines only that something is rather than what it is. Apart from form, matter is indeterminate between different kinds of being; apart from matter, form is untethered from this or that individual; apart from esse essence is nothing; and apart from essence, esse is completely undiversified.

Because it is a part of essence, form of itself is in some sense indifferent to being simpliciter, although not indifferent to being this or that kind of thing. Thus, form can only operate insofar as it is, and therefore depends on the actuality of esse in order to impose its actuality upon matter. The same goes for any other actuality in or from a thing’s essence, which is why esse is called the actuality of all actuality, since by it all other actualities of a thing are able to operate in their distinctive ways. This is why Aquinas concludes that the form (or any principle or combination of principles in the essence) cannot be the cause of esse, since such operation would require the thing to already exist, meaning that the effect (esse) causally precedes itself, which is absurd. Given the causal principle, then, it follows that a thing must receive its esse from an outside cause. All in all, then, we have existential inertia in the sense of “substantial” inertia described above, but not in the sense of “esse” inertia.

5. Some more clarifications

As before, it is worth clarifying a few important things.

First, we may wonder why Aquinas insists that the cause of esse must “be caused as by an efficient cause”? The reason becomes clear once we understand what is meant by the term: an efficient cause of some actuality A is something extrinsic to A and actual in such a way as to actualize the potential for A. Since essence is really distinct from esse, if any of the principles of nature were to cause esse they would be extrinsic to and therefore efficient causes of the esse. Often, the A in question is a form, which continues to actualize the matter as an intrinsic principle of a thing. Even when a substantial form preserves an accidental form (“accidental” inertia) the two are not really extrinsic to one another, for the latter just is a qualifier of the former. So, when it comes to esse, the form as formal cause cannot be the cause because it is part of the essence, so we only need consider the form as an efficient cause.

Second, we may grant that an extrinsic cause is needed in order to cause the initial composition between essence and esse, but why is one needed to preserve it in each subsequent moment? Because there is no “form”—or indeed, any actuality—to preserve it once the cause ceases their action. When a person stops accelerating a brick, so too does the brick stop accelerating, instead continuing along whatever velocity it had when the person let go. Both the acceleration and the velocity are actualities in the brick, but only the velocity is preserved. This is because the brick does not have a form that can maintain its acceleration, only one that can maintain its velocity. The general point here is that potentials do not intrinsically stay actualized, but rely on a deeper “inertial actuality” (a form) to preserve them as such. Potentials are indifferent to whether they’re actualized, for they merely ground a thing’s openness to being actual in a particular way. Preservation, however, is a way of being persistently actual, and therefore needs to be accounted for by actualities. When it comes to the preservation of the process by which a thing is constituted (life, dynamic structure, etc.) this inertial actuality is the substantial form, but everything in the essence is in potential to the esse and therefore there is no actuality to preserve their composition.

Third, as a follow-up to this, we may wonder why it can’t be that the principles of a thing’s nature from an earlier time are what cause its esse at a later time? But this won’t do either, because efficient causation is fundamentally simultaneous, and causation across time is a result of these inertial actualities that are absent with esse. Efficient causation occurs when an agent, by some actuality in itself, actualizes a potentiality in a patient. Insofar as an agent acts on a patient we have action, and insofar as a patient is acted upon by an agent we have passion. But further reflection shows that action and passion are really just the same reality considered from different perspectives, since both are realized insofar as the agent influences the patient. That is, the actuality of the agent becomes action for the same reason that the potentiality in the patient becomes passion, namely the actualization of the latter by the former. Action and passion are simply two ways of conceptualizing the dependence of the actualized potential in the patient upon the actuality in the agent. “So there is only one actuality involved for them both, just as there is the same interval from 1 to 2 as there is from 2 to 1, and just as uphill and downhill are identical.” (Aristotle, Physics III.3)

Non-simultaneous causation occurs when the patient contributes something to the preservation of the effect itself. Consider again the brick being thrown. The fundamental causation is simultaneous: the person accelerating the brick (action) and the brick being accelerated (passion) are the same reality considered from different perspectives, which is why the brick stops being accelerated once it leaves the person’s hands. After this, the brick itself preserves its velocity until it breaks the window. The person causes the window to break in the sense of imparting the velocity to the brick, but their action ceased earlier, and its effect has since been preserved by the brick. This looser and diachronic version of causal dependence presupposes that the patient has existence outside of the action of the agent, whereby it contributes this preservation of the effect beyond the action of the agent. It is therefore not applicable to the causation of esse, wherein the very existence of the patient is what is being caused.

Thus, the only causation applicable to esse is the more fundamental simultaneous causation: the action of the agent causing a thing’s esse must be the same reality as the patient receiving it. But this excludes the possibility of a thing causing its later esse from an earlier time.

6. Objections to simultaneous causation

The point of all is not to provide some new response to the challenge of existential inertia, but to show that Thomistic metaphysics had already accounted for it to some degree, and to clarify some aspects of it for our current context. Of course, Schmid and Linford are not unaware of the Thomistic arguments, and so it is worthwhile to consider some of the objections they raise against it, implicitly and explicitly.

The first objection I’ll consider is raised against the notion of simultaneous causation, which comes in the section where they discuss transtemporal accounts of existential inertia. To set us up, consider this point made just before the discussion on simultaneous causation begins:

One question for causal transtemporal accounts is: when is the causing taking place? In response, we note that this question is ambiguous between (i) ‘when is the cause causing?’, and (ii) ‘when is the effect effecting (i.e. being effected or brought about)?’. The answer to the former is the immediately prior moment, while the answer to the latter is the immediately posterior moment. And there is no tertium quid; we need not (and, we suggest, should not) reify the ‘event’ of the cause’s causing the effect. There’s just the cause and the effect, the former of which is immediately temporally prior to the latter. (So You Think, 5.2, emphasis original)

Despite this sounding like it’s diametrically opposed to what I’ve just said about causation, the Aristotelian and Thomist actually agree that this accurately describes a large class of causation! A distinction is commonly made between causing the being of something and causing its becoming. To illustrate the difference, the person throwing the brick causes the becoming of the brick’s velocity but the being of the brick’s acceleration. Similarly, the builders of a house cause the becoming of the house but the being of the house’s construction. When causing the becoming of a thing, the agent causes the change(s) that result(s) in the thing coming into existence, but not the continued existence of the thing once it exists. After all, once a thing exists it is no longer becoming, and so the agent no longer has anything to cause. Thus, returning to the quote, if the “cause” refers to the agent causing the change leading up to the thing’s existence (the becoming) and the “effect” refers to the thing’s existence, then it’s spot on. There is no moment when both the thing is becoming and has become, for this would be a contradiction. Rather, there is some moment t for which we can construct two open intervals I1=(t1, t) and I2=(t, t2), such that I1 encompasses the end of the change of becoming and I2 encompasses the start of the thing existing.[9]

None of this undermines the Aristotelian position on the simultaneity of causation, however. The non-simultaneity of becoming is simply a consequence of its non-fundamentality: the agent causes the becoming at t precisely by causing the process of change leading up to it in the interval I1. It is this process of change which is both the action of the agent and passion of the patient, and therefore where we should be looking for causal simultaneity. As in all cases of fundamental (or per se) causation, the action and passion last only as long as the agent acts, so that if the agent stops halfway through, then so too does the change, preventing the becoming at t from ever occurring—the brick is not accelerated to the same velocity, and the house remains unfinished. As we saw above, then, in order for this sort of non-simultaneous causation to occur, the effect must have some existence outside of the action of the agent so that it does not go out of existence the moment that action ceases. Such a condition cannot be met when the effect in question is the very esse of a thing.

The trouble is that simultaneous causation is not obviously consistent with an orthodox understanding of relativity. As we’ve discussed, orthodox interpretations of relativity entail that objective simultaneity does not exist. Friends of simultaneous causation would be right to point out that they use the term ‘simultaneous’ differently from how that term is deployed by physicists… For physicists, to say that two numerically distinct space-time points p1 and p2 are simultaneous is just to say that p1 and p2 occur at numerically the same absolute time, that is, that p1 and p2 are instantaneous. Friends of simultaneous causation should not be interpreted as endorsing the view that causes are instantaneous with their effects. For that reason, simultaneous causation cannot be ruled out merely on the grounds that relativity rules out objective instantaneity. However, friends of simultaneous causation move too quickly if they conclude that simultaneous causation runs into no problems at all from relativity. The trouble is that the failure of objective instantaneity makes objective concurrence much more difficult to understand. And without objective concurrence, standard accounts of how causes can be simultaneous with their effects break down. (So You Think, 5.2)

As helpfully pointed out in this objection, there are different senses of “simultaneous” at play here, and so it is incumbent upon the Aristotelian and Thomist to explain what sort of simultaneity they are affirming in the case of causing esse. After the quoted passage, Linford goes on to consider possible responses that the defender of simultaneous causation might give, involving things like alternate interpretations of special relativity which introduce a preferred reference frame (a move I consider to be contrary to Aristotelian presuppositions), reification of Feynman diagrams (which I readily admit to not understanding), and so on. It seems to me that the Aristotelian position is far more basic than these considerations, and limited in scope to what I have termed fundamental causation, which is that to which other forms of causation can be reduced—as we have already done in the case of preservation of effects and becoming.

The basic reason for affirming the simultaneity of fundamental causation is that action and passion are really identical to one another—whatever we think about simultaneity, surely everything is simultaneous with itself! But let us unpack this a bit more. In fundamental causation we are not envisioning two distant events occurring at the same time, but one event occurring in the place where agent and patient are in contact, for the power of a physical agent is limited to where it is. In fact, since the Aristotelian thinks that time supervenes on change, and that simultaneity is fundamental to change, any characterization of the latter in terms of the former would necessarily be secondary to something more fundamental.

What is it, then, for the act of the agent to be “simultaneous” with the change of the patient? It is that a necessary condition for the change occurring is the causal presence of the act of the agent, where “causal presence” captures something more general than both spatial presence (here) and temporal presence (now). In general, what is necessary is that the act of the agent and the potential of the patient be such that the former influences the latter, resulting in the one reality that is both action and passion. In the case of physical things, this requires both spatial and temporal presence, for both of these limit the influence of the physical cause—a person cannot throw a brick if they are not touching it, nor if they live before or after it. The point is that when we are thinking about fundamental causation between physical things, it is something which is mediated by points of contact between physical things, so that cause and effect can be co-present in time (simultaneous) because they are co-present in space (local). While special relativity raises questions about simultaneity at a distance, it has no problem with simultaneity between things in physical contact with one another.

We may wonder about causal influences that are not completely local, such as the propagation of motion through a physical object. For example, by waving my hand rapidly I cause a wave to propagate down the length of a rope. The further down the rope we go, the less local and simultaneous the effect is with the movement of my hand. Even after I let go of the rope, the wave continues to propagate throughout the rope. But of course, this is simply another case of non-fundamental non-simultaneous causation, where the effect is preserved in the patient after the agent has caused it. In this case, the form of the rope orders it to an equilibrium state, which it eventually reaches after the agent has let go for long enough. Because the form is realized in matter, it does not instantaneously move the rope to this state, but does so gradually as the energy from the agent dissipates through it. While the details are different, the same principles are at play, wherein the nature of the patient allows for the preservation of the effect of the agent. We have already explained why this is not relevant to the question of causing esse.

With all of this said, we should ask whether the cause of esse could even be physical, for if not then concerns about relativity of simultaneity, while important, are less pressing. Since esse is really distinct from essence, it would seem to be an effect outside of natural categories. The laws of nature are the laws of natures, but esse is that in virtue of which natures can exist and operate at all. It seems likely, then, that the cause of esse, in physical things, does not do so through the exertion of physical forces, the imposition of energy, or any other such things. Rather, it seems likely to be something non-physical, and therefore not obviously subject to the considerations of special relativity. The notion of “causal presence” is applicable to these cases, although the details will have to be left to another occasion. I simply raise this as a noteworthy consideration, which is once more a consequence of the real distinction.

7. Objections to ontological pluralism

This brings us to the objection raised by Schmid and Linford to other aspects of the De Ente argument, based on its apparent commitment to something called ontological pluralism (So You Think, 7.13). The objection is stated in a lengthy discussion, and for those interested in going deeper I would recommend reading it in its entirety. For the sake of my discussion here I will summarize it as follows: some aspects of the De Ente argument seem to commit us to a version of ontological pluralism, but we should not accept ontological pluralism, and therefore we should not accept the De Ente argument.

Starting with the major premise first, ontological pluralism is the position that there are different ways of being. It is contrasted with ontological monism, which holds that everything enjoys the same kind of existence. You will recall that the multiplicity argument established that in all but at most one thing essence is really distinct from esse, while the causal principle established that the esse in all such things is caused by something else. Since each of these only contribute potentiality to their existence, the series of causes is essentially ordered and therefore has a primary member whose essence is really identical to esse. Thus, there is exactly one thing which is pure or absolute esse, which we call God. But note that God must exist in a very different way from the rest of reality: his essence just is esse, whereas in everything else esse is received into essence; his esse is uncaused, whereas everything else is caused; he is pure actuality, whereas everything else is mixed with potentiality. Given that God and creatures exist in these different ways, we have ontological pluralism.[10]

In fact, there are other kinds of ontological pluralism as well. The real distinction implies that essence stands to esse as potentiality to act. And as noted by Schimd and Linford, potentiality and act do not exist in the same way, as I briefly pointed out in my recent post these exist in different ways—act is that in virtue of which a thing is, but potentiality only exists because of act. Additionally, in the final chapter of the De Ente, Aquinas discusses the essences of accidents as opposed to substances, and these differences translate to a difference in being. All of this is a consequence of the Aristotelian dictum that “being is said in many ways” (Metaphysics Γ.1) Indeed, in his commentary on the Metaphysics, Aquinas gives us a taxonomy of the different modes of being and how they relate to one another. Since the details will be relevant to my later discussion, here’s the whole passage:

But it must be noted that the above-mentioned modes of being can be reduced to four.

(1) For one of them, which is the most imperfect, i.e., negation and privation, exists only in the mind. We say that these exist in the mind because the mind busies itself with them as kinds of being while it affirms or denies something about them. In what respect negation and privation differ will be treated below.

(2) There is another mode of being inasmuch as generation and corruption are called beings, and this mode by reason of its imperfection comes close to the one given above. For generation and corruption have some admixture of privation and negation, because motion is an imperfect kind of actuality, as is stated in the Physics, Book III.

(3) The third mode of being admits of no admixture of non-being, yet it is still an imperfect kind of being, because it does not exist in itself but in something else, for example, qualities and quantities and the properties of substances.

(4) The fourth mode of being is the one which is most perfect, namely, what has being in reality without any admixture of privation, and has firm and solid being inasmuch as it exists of itself. This is the mode of being which substances have. Now all the others are reduced to this as the primary and principal mode of being; for qualities and quantities are said to be inasmuch as they exist in substances; and motions and generations are said to be inasmuch as they are processes tending toward substance or toward some of the foregoing; and negations and privations are said to be inasmuch as they remove some part of the preceding three. (Metaphysics IV, Lecture 1, 540–543)

The upshot of all of this is that it seems quite right to say that the De Ente argument—as well as the broader Aristotelian metaphysical framework as a whole—commits us to some version of ontological pluralism. This brings us to the minor premise of the argument from Schmid and Linford, namely that we should not accept ontological pluralism. Here they apply an argument from Trenton Merricks, which goes something like this:

- Ontological pluralism cannot accept a notion of generic existence that holds true for all things.

- Without a notion of generic existence the ontological pluralist cannot state their position.

- Therefore, we should not accept ontological pluralism.

Of course, you’d need to add some more “connective” steps in order to fully justify the move from (1) and (2) to (3), but this summary is good enough for our purposes here.

7.1. Focality and “generic existence”

The “generic existence” of this sub-argument refers to a common existence shared by all existing things. This is what corresponds to or grounds the fact that things exist rather than not. Even if God and creatures exist in different ways (so the thought goes), they have in common the fact that they exist at all, and this is what generic existence captures. To generically exist is “to exist, or to have being, or to be something” (Merricks 2019, p. 599) This turns out to be a fairly minimal, and therefore flexible, notion, as we shall see in what follows.

Why think that ontological pluralism cannot accept generic existence? Three reasons are given: (i) it goes contrary to the core insight of ontological pluralism, (ii) it renders the notion of different ways of being superfluous, and (iii) it is at odds with traditional defenses of ontological pluralism. Let’s take each of these briefly in turn.

Regarding (i), Simmons correctly notes that there is an important difference between how Merricks understands the core insight of pluralism and how pluralists understand it:

Thus, to be a pluralist is, at least as I understand it, to be minimally committed to the claim that there are ontological differences between certain entities, differences which lie not in what these entities are, but in the ways of being these entities enjoy. This is not how Merricks understands pluralism. He sees the pluralist’s core insight not as a simple recognition of ontological difference, but as a complete denial of ontological similarity (where we can say that there is an ontological similarity between two entities just in case there is some way of being that these entities alike enjoy).[11]

It seems to me that the Aristotelian and Thomist would agree with Simmons here. That is, a recognition of different ways of being does not entail that these different ways don’t share something with one another, in virtue of which each can be said to be rather than not. We would say, for instance, that angels exist in a different way than humans, since the former do not depend on matter for their being whereas the latter do. And yet despite this difference there is still some unity in these two ways of existing, since they both exist as substances.

Another example is the multiplicity argument. There we considered three ways in which esse, considered abstractly, might be plurified. What we landed on was that it is plurified precisely by existing absolutely on the one hand (God), and received on the other (creatures). But note that despite resulting in multiple kinds of being, this argument assumes that there is some kind of unity between these two cases, in virtue of which they can be said to plurify something common. What was that something common? It was esse, which at that point was just understood as that in virtue of which something is, which sounds a whole lot like “generic existence”.

The passage from Aquinas quoted above is another example which we will consider in more detail shortly. The upshot of these examples is that the pluralist commitment to multiple ways of being does not require that they be completely disconnected from one another. For the Aristotelian, there may well be shared aspects between the modes of being, among which we may find some notion of generic existence. All that we deny is that there is one distinct mode of being shared by all.

Regarding (ii), we may wonder what benefit there is in affirming different modes of being if we accept some notion of generic existence? Why not simply say that everything enjoys generic existence as the only mode of being, and that all differences are differences in essence? This would certainly be a live option at the outset of our theorizing about essence and esse, but it gets excluded by later results. For example, the modality principle[12] says that whatever is received is received according to the mode of the receiver, and the real distinction tells us that essence receives esse. Thus, although the same thing is received by everything, namely esse, once it is received is limited and qualified by that which receives it, thereby resulting in esse of a different mode. Interestingly, this suggests that there is some sense in which all things enjoy the same sort of existence. Consider the relationship between absolute esse and received esse: received esse just is absolute esse qualified by this or that essence. Absolute esse is unreceived and therefore infinite, whereas received esse is finite. Thus, received esse “grasps a part” of absolute esse, which is to say that it participates in it.[13] There is a sense, then, in which all existence ultimately comes down to absolute esse. The phrase “ultimately comes down to” leads us to the final reason.

Regarding (iii), I struggle to see how it is true for Aristotle and the Scholastics who followed him. As Owen famously showed,[14] earlier in Aristotle’s career he rejected the possibility of a science of being qua being because of the lack of unity in the notion of being—there are only different kinds of being, he reasoned, and therefore no unified subject for the study of being as such. On this earlier account there was no place for an overarching field of metaphysics, but only the “departmental” fields like physics, ethics, and so on. But later, by the time of Metaphysics Γ, Aristotle had found a way to recognize both the diversity of being and its fundamental unity, thereby opening up the path for metaphysics as the study of being qua being. This result seems directly applicable to the question of generic existence, since the same unity which makes the science of metaphysics possible would presumably also fulfill the requirements of generic existence.

So, how did Aristotle affirm the unity of being without rejecting its diversity? According to Owen, he introduced the notion of focal meaning.[15] Being is said in many ways, yes, but all these ways are understood with reference (and are reducible) to one, namely substance. Substance is therefore the focal way of being. This is what Aquinas is saying in the earlier quote, when he explains that “all the others are reduced to this as the primary and principal mode of being.” He goes on to show how each mode of being in some way includes substance within its definition, and is therefore only intelligible in terms of the substantial mode of being. As such, each mode of being can be translated into the substantial mode of being together with a bunch of qualifications. Although potentiality and actuality are not discussed on their own, they are included as principles of the modes which are discussed—potentiality underlies privation, change, and accidents, for instance. The same goes for other principles of being, such as form, matter, essence, and esse. Furthermore, even though God and creatures exist in different ways, they are still both substances, which is to say that each exists “in reality without any admixture of privation, and has firm and solid being inasmuch as it exists of itself.” This predicate has the same meaning in both cases, while the difference in ways of being arises from the fact that the reasons for why it is true in each case differ.

Does all of this amount to generic existence? Perhaps. It doesn’t give us a distinct mode of being which all things share, but it does give us a way of unifying all modes of being in relation to the focal mode, and a common way of understanding this mode even while it obtains in different ways. Whether this is enough will depend on premise (2) of the argument, to which we now turn.

7.2. Stating the pluralist position

Why think that without a notion of generic existence the pluralist cannot state their position? Each mode of being i gives us a domain of existential (∃i) and universal (∀i) quantification, which are related as usual. If there is no generic existence, then there is no absolutely universal domain of quantification, so that we could not state our position in terms of a universal quantification. Consider, for instance, the statement, “everything exists according to mode 1, or mode 2, etc.” Symbolically, this would translate to: (∀x)[(∃1y)(y=x) or (∃2y)(y=x) or …]. But notice that the universal quantifier here is not bound to any domain, and therefore does not correspond to any mode of being—it must instead correspond to generic existence. In order to address this, the pluralist would need to state their view with only the qualified quantifiers. Merricks gives this example for a pluralist who believes in two ways of being, which we’ll call a “2-pluralist”:

(∀1x)[∃1y(y=x) or ∃2y(y=x)] and (∀2x)[∃1y(y=x) or ∃2y(y=x)] and (∃1x)(x=x) and (∃2x)(x=x)

However, while this affirms something the monist cannot, it does not secure 2-pluralism over 3-pluralism, or 4-pluralism, or 5-pluralism, etc. After all, the n-pluralist believes in modes 1 and 2, and so can affirm the above statement, but they also believe in modes 3, 4, 5, …, and n. Thus, the above statement does not affirm something uniquely 2-pluralistic, and the same problem would best any n-pluralist. Merricks considers various other ways in which the pluralist might fix this problem, and finds all of them wanting. By contrast, he finds multiple acceptable ways of stating monism, for instance: (∃x)(∀y)(if x is a way of being and if y is a way of being, then y=x).

In evaluating this argument from a Thomistic perspective, three points seem most salient. First, the version of generic existence based on focality seems sufficient to state an n-pluralist in the way required by the argument. Second, the argument incorrectly assumes that the n-pluralist position needs to be stated extensionally. And third, the Thomist is arguably not even an n-pluralist and therefore not the target of the argument.[16]

Although the Aristotelian and Thomist do not grant that generic existence is some distinct way of being, through focality they can recognize the unity of being in relation to a primary way of being. We may therefore speak of generic existence as a shared feature between all ways of being, namely that in virtue of which anything is rather than not. There is a common reason why accidents, motion, and privations exist, because each is reduced to substance. In the argument from Merricks, each mode of being results in its own range of quantification, but there is no reason to think that ranges of quantification could not also arise from shared features of modes of being. In particular, since all modes of being are reduced to the focal one, there is a universally shared feature which therefore results in a universal range of quantification over those things which exist rather than not.

The second point is that the n-pluralist need not state their position by quantifying over the extension of being—an assumption which does not start with Merricks, but which undergirds his argument nonetheless.[17] I will not say much about this, since I’m both insufficiently informed on the matter,[18] and the point is primarily logical rather than metaphysical.[19] The basic point is this: I see no reason why the 3-pluralist (for example) could not state their position simply as, “the ways of being are x, y, and z.” That’s it. The basic subject of the pluralist position is being itself rather than all the individual beings out there, and thus should be found in the intensional demarcation of the domain of ways of being rather than an extensional quantification over each being. Notice also that there is no need for additional statements which imply quantification, like “and there are no others” or “and there are only three,” because this statement defines the entire domain as such rather than quantifying over the elements of the domain. Once we have this basic statement in place, we are then free to quantify universally over everything (if we so wish), since it is just the quantification of the extension of each of the ways of being.

The third point is that it’s not clear to me whether the Thomist is an n-pluralist at all, and therefore whether the present argument is applicable. Merricks argues that it is not possible for a pluralist to state that there are exactly n ways of being, but what if the pluralist doesn’t think of pluralism in that way? Without a demonstration that a certain collection of ways of being is both mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive, the pluralist may well be content simply to state that there is more than one way of being, while leaving it as an open question just how many there are or how they are related. In Thomistic metaphysics, there are plenty of divisions of being: Aristotle’s ten categories, Aquinas’s four modes enumerated above, the three modes of participation, the two-way distinction between absolute and received esse, and so on. But these overlap one another in various ways, and don’t include things such as abstract objects (which the Aristotelian denies exist apart from our abstractions) and merely possible concrete objects. Part of the import of the maxim “being is said in many ways” is apparently the fact that we can approach being from various perspectives, even if there is an overarching unity of method and subject matter. Furthermore, in each case we are able to articulate the number of modes in terms of the philosophical tools we had to develop in order to arrive at our division: in the case of the absolute-received division of esse, for instance, we used the categories afforded to us by the multiplicity argument.

8. Conclusion

This brings me to the end of my (relatively) “brief” Thomistic appraisal of existential inertia. I think that the intuitions that might draw us to existential inertia are tracking something true, but that deeper analysis shows that there is an extra dimension that needs to be considered. The argumentation in the De Ente shows that essence is really distinct from esse in all but one thing, so that while substantial form is a principle of existential inertia, this still depends on an external cause. While at first it may seem a contradiction to say that existential inertia requires an external cause, ultimately the real distinction shows us that the form-matter distinction is caught up in a higher essence-esse distinction, so that while existential inertia occurs in the former (form preserves matter’s being something) the external cause is needed in the latter (esse makes essence be at all). Non-simultaneous causation does not help here, and objections to simultaneous causation fail to reckon with the Aristotelian justification and application of it to fundamental causation. Objections to ontological pluralism, to which the De Ente arguments commits us, similarly do not touch the Thomistic version of it. All-in-all, then, the Thomist is happy to affirm existential inertia, but cautions that the picture is more complicated than initial impressions might appear.

[1] We may wonder why they could not be entirely the same without being exactly the same thing? As will become clear in the clarifications section, it is because such a situation is posterior to what we’re considering here. Specifically, it assumes that we have two distinct things which share something in common, which is precisely what we’re trying to analyze. We cannot therefore take it for granted in the analysis itself. Instead of thinking of “same” in terms of “similar”, we should think of it in terms of “one”.

[2] Aquinas refers to this as a separated X, because an unreceived X is separate from those things which may receive it.

[3] The case where both common and diverse are receptive of one another may be analyzed in terms of (1) and (2), and therefore need not be an alternative in our taxonomy.

[4] To be absolutely X is to be X without qualification, while to be purely X is to be X without anything else added. In this case, purity and absoluteness are the same, since something is added to X if and only if it qualifies X in some way.

[5] This is the reception principle discussed in my post, “Three principles about act and potency.”

[6] Peter Forrest, “The Identity of Indiscernibles,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

[7] For a discussion of this sort of reasoning by Aquinas in a different context, see Michael Augros, “Twelve Questions about the ‘Fourth Way.’” The Aquinas Review 12 (2005).

[8] For a detailed discussion on this notion of esse tantum, see Gaven Kerr, Aquinas’s Way to God: The Proof in De Ente et Essentia, 150–72.

[9] For a detailed discussion on instantaneous change from an Aristotelian perspective, see David Oderberg, “Instantaneous Change Without Instants.”

[10] In a post from a few years ago, “Potentiality from first principles,” I attempted to avoid the commitment to ontological pluralism. Since then, thanks to comments by Rob Koons and Joe Schmid on that post, I have realized that I had misunderstood what it would mean for actuality to be generic existence (as I had proposed). This would entail that potentials are actualities, which is false. In this post I correct this, and cash out the Aristotelian position in terms of the focal meaning of being. This approach was suggested by Koons in his comments (although any remaining misunderstandings are of course my own).

[11] Byron Simmons, “Ontological Pluralism and the Generic Conception of Being,” Erkenntnis 87 (2022), 1275–1293.

[12] This is one of the principles discussed in my post, “Three principles about act and potency.”

[13] See my post, “Indeterminacy, infinity, and participation.”

[14] G.E.L. Owen, “Logic and metaphysics in some earlier works of Aristotle,” in Aristotle and Plato in the Mid-Fourth Century: Papers of the Symposium Aristotelicum held at Oxford in August, 1957, eds. I. During and G.E.L. Owen.

[15] G.E.L. Owen, “Logic and metaphysics in some earlier works of Aristotle.” For a helpful discussion on the relationship between focality and analogy in Aristotle, see Alexander Edwards, “Aristotle’s Concept of Analogy,” Dionysius XXXIV (2016), 62–87.

[16] To clarify, the first point is that Thomism has the conceptual tools necessary to state n-pluralism, while the third point is about whether the Thomist would in fact affirm it.

[17] In addition to the paper cited earlier, I see that Byron Simmons has another paper on this very topic, although I have not spent much time with it. I reference it simply for those interested in further reading: “Should an Ontological Pluralist be a Quantificational Pluralist?”, Journal of Philosophy 119 (2022), 324-346.

[18] My exposure to logic is through my studies in pure mathematics rather than philosophical logic, nevermind the role of extension in the articulation of more forms of ontological pluralism. This second point is included largely as a way of me thinking through how Aristotle or Aquinas would have articulated their view of ontological pluralism, since neither had access to first-order predicate logic as we typically use it today.

[19] Although I find this second point relevant, Merricks explicitly says his concern is metaphysical, which is why I do not belabor the point.

Leave a comment